The TypoArabic research project concluded on 3 June 2022, and I am delighted to announce that its principal output, the edited volume Arabic Typography: History and Practice, has now been published by niggli. As foreshadowed in a post on the TypoArabic blog in June 2021, a group of esteemed colleagues were invited to contribute chapters drawing on their own research. Despite demanding day jobs, everyone stayed the course — a rare achievement for edited volumes and a demonstration of the exceptional commitment by the authors.

The book opens with a preface by Robert Bringhurst, who reflects on the importance of looking beyond your immediate typographic surroundings — in a manner that is more engaged than a mere ‘tourist jaunt’. Bringhurst’s framing of this book as a gateway to one of the world’s great scriptorial traditions provides an ideal entry point to the following discussion of Arabic typography and type-making.

Taking over, Gerry Leonidas’s introduction considers how typographic practice has been reflected in writing, how it tended to ‘think about itself’. He discusses the challenge that typography, ‘a domain of practice’, has had in finding modes of discourse appropriate to its nature, and accommodating sources that fall outside the established genres of academic literature. Reviewing a selection of key historical texts on typography, Leonidas identifies a tendency towards one-dimensional descriptions of techniques and monolithic prescriptions of practice that reflect commercial interests and single, isolated viewpoints with a predominantly anglocentric tilt. Reflecting on their scope of discussion, applicability, and contextualisation, Leonidas’s piece throws the exclusion of most of the world’s writing systems from typographic literature into sharp contrast. He identifies a flattening of complexity in discourse that extends into practice: a trend that continued from manual craft all the way into digital typography, dominated by an industry whose geographic location perpetuates narrowly anglophone approaches. Whilst singling out important contributions that serve as correctives to this trend, he concludes that ‘across writing systems the bibliography on research-informed practice in typography is partial at best’. Against this background, Leonidas finds that owing to the multitude of perspectives of Arabic Typography: History and Practice, its foundation in research, and its transparent arguments, ‘it can be claimed to represent a paradigm shift for typographic scholarship, across writing systems.’

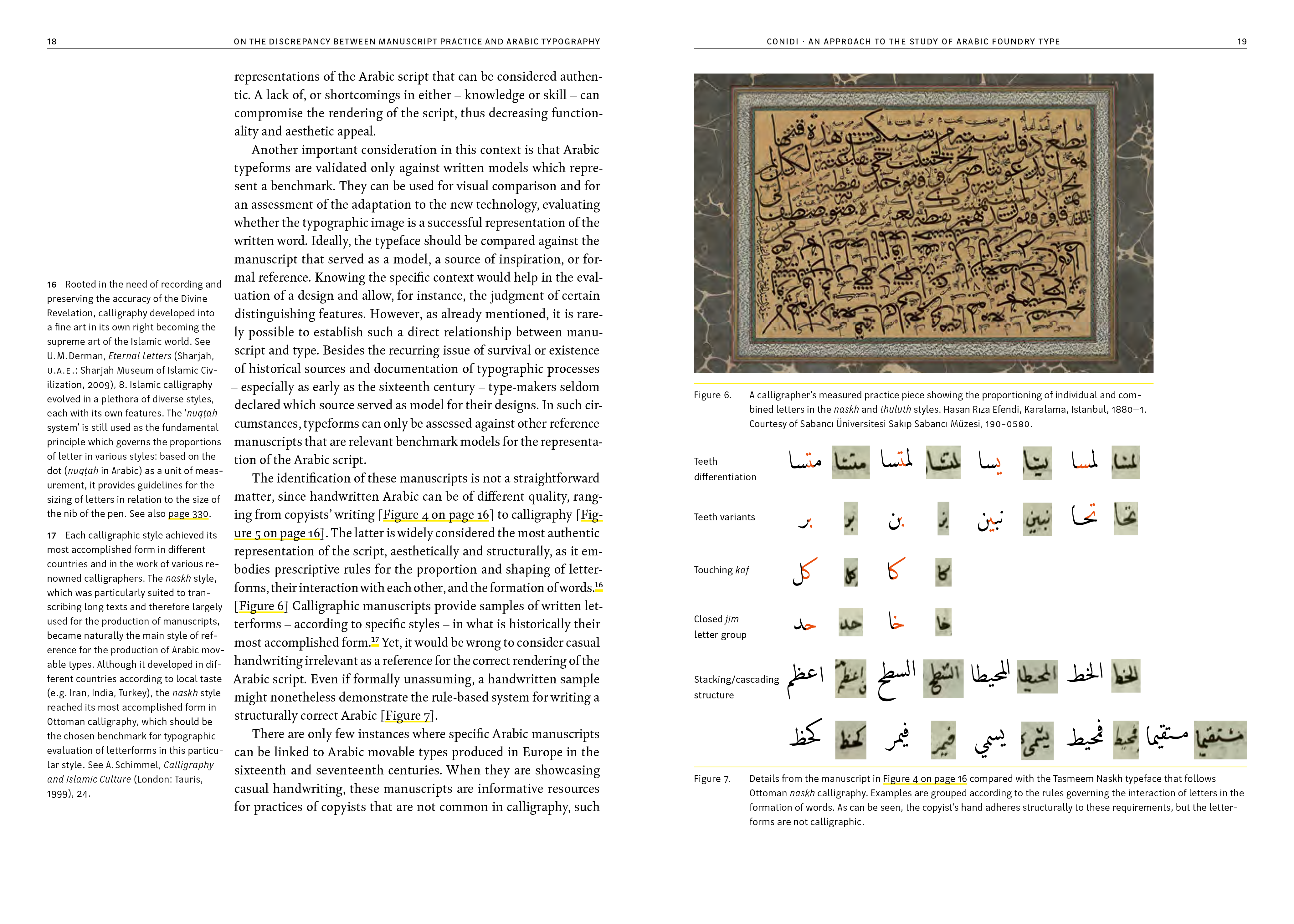

Continuing in this reflective vein, Emanuela Conidi offers a thorough discussion of her approach to the study of Arabic foundry type. Considering the historical circumstances of practice – from early modern Europe to the last pre-industrial Arabic fonts made in the Middle East – she emphasises the influence that various agents and their respective means had on print artefacts. Conidi scrutinises the bearing that sources – both material and personal – had on printer’s types, considering factors such as script competence, language proficiency, and technical mastery. She identifies how manuscripts – of varying quality – influenced punchcutters, and shows in great detail how various Arabic metal fonts replicated, interpreted, and diverged from characteristics of the Arabic script. Raising concepts such as ‘unintended’ as opposed to ‘deliberate’ variation of letterforms in manuscript practice and print, Conidi’s visually rich discussion, is a tour-de-force of typographic scholarship. In a concise overview of the first two centuries of Arabic printing, she highlights milestones of type-making, analysing the respective achievements, shortcomings, and influences on subsequent contributions. The resulting picture complicates established narratives of typographic history. In her concluding discussion, Conidi considers how the in-depth analysis of foundry type and its juxtaposition with manuscript models can yield insights into type-making processes. By means of select case studies, she demonstrates various approaches to the typographic interpretation of the Arabic script, casting light on the influence of tools and script competence on type-making.

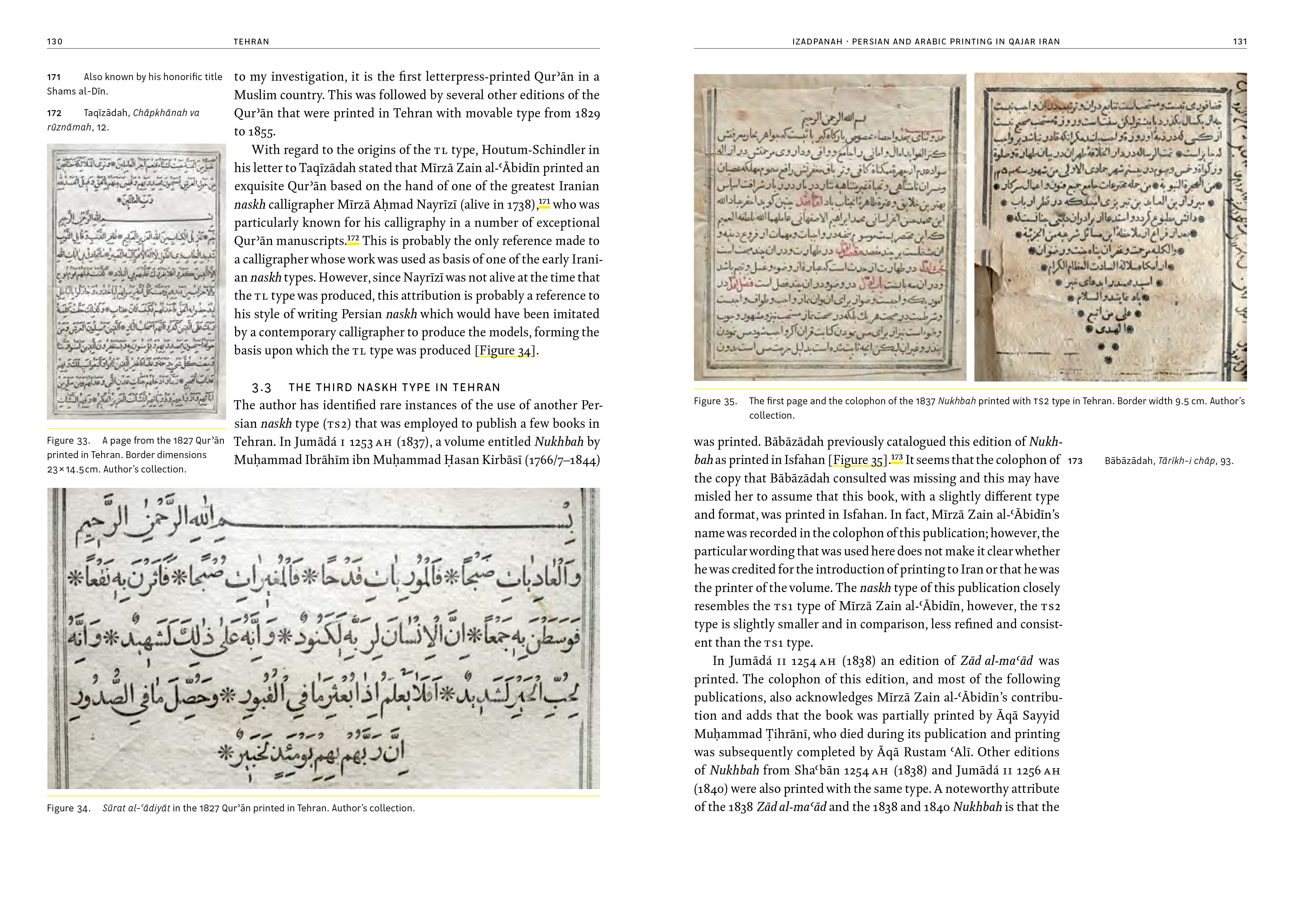

Borna Izadpanah, in turn, focuses on typographic printing in Qajar Iran from 1818–1900. Drawing on a spate of historical sources, he discusses in unprecedented detail when and how Arabic movable type was introduced to Iran, revealing new details and correcting earlier accounts. Quoting from original documents, Izadpanah adds depth and context in a manner that enriches historical developments with a sensitivity for the human dimension, and amplifies historiography in our field. In the process, he identifies and discusses unknown editions, overlooked copies, and their respective types, recalibrating the status quo of Persian printing history. Starting with the unresolved questions surrounding the first printed book in the country, Izadpanah charts the following developments in Tabriz, Tehran, and Isfahan, the key cities for the emergence of typographic print in Iran. Further to a chronological account, he considers the origins of typefaces, the genres of books, and revisits the established historiography of printed Qur’āns, challenging central assumptions of the field. Whilst focussed on history, Izadpanah’s essay also discusses the use of illustrations and aspects of book layouts that emerged in Qajar Iran, broadening the perspective towards typographic design and contemporary applications. Thus, a line is drawn from nineteenth century foundry type to the work of Hossein Abdollah-zadeh Haghighi, a central figure of Iranian type design in the twentieth century. Izadpanah’s piece concludes with an overview of all Persian naskh types identified during the era under review and makes a powerful case for the existence of an independent, indigenous type-making culture in Qajar Iran.

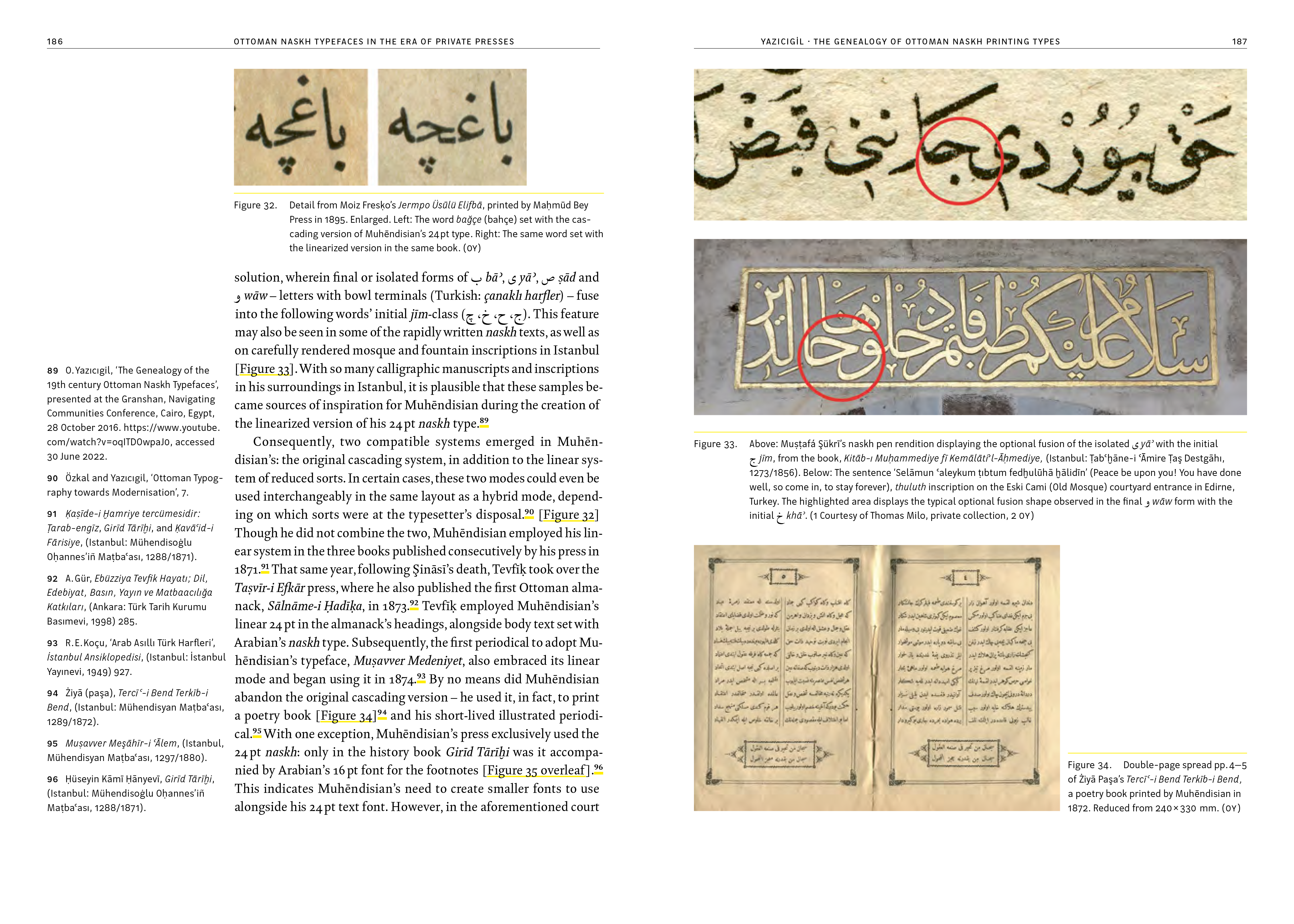

Onur Yazıcıgil investigates the history of Ottoman naskh printing types, and stitches together the most complete account of the subject yet. His piece begins with a concise overview of the origins and development of the calligraphic style, discussing key protagonists in its evolution and the specific visual qualities of Ottoman naskh. Turning to typography, Yazıcıgil begins his account with a concise review of the work of the Müteferriḳa press, evaluating its typeface and assessing its contribution to the further development of the craft in the region. Whereas Müteferriḳa’s pioneering work has received considerable attention in the literature, Yazıcıgil breaks new ground in his in-depth discussion of the types used at Ottoman presses during the nineteenth century. Starting with Bōghos Arabian’s naskh font for the Mühendisḫāne — the first name of the Ottoman government printing house — and continuing with work done at private print shops, Yazıcıgil combines a detailed analysis of typeforms with a contextualisation of typographic achievements within wider historical circumstances. Using original sources from the Ottoman Imperial archives, he draws a finely nuanced picture of the Arabic type-making trade in Istanbul, touching on economics, competition, and censorship. The portrait that emerges is one of a multi-ethnical and cross-confessional craft that operated at the interface of a modernising society with a traditional bureaucracy and state. Whilst formally rooted in tradition, Ottoman type-makers and printers used current techniques, were connected with fellow colleagues across the Middle East, in Europe and beyond, and contributed a central strand to the formation of a modern society.

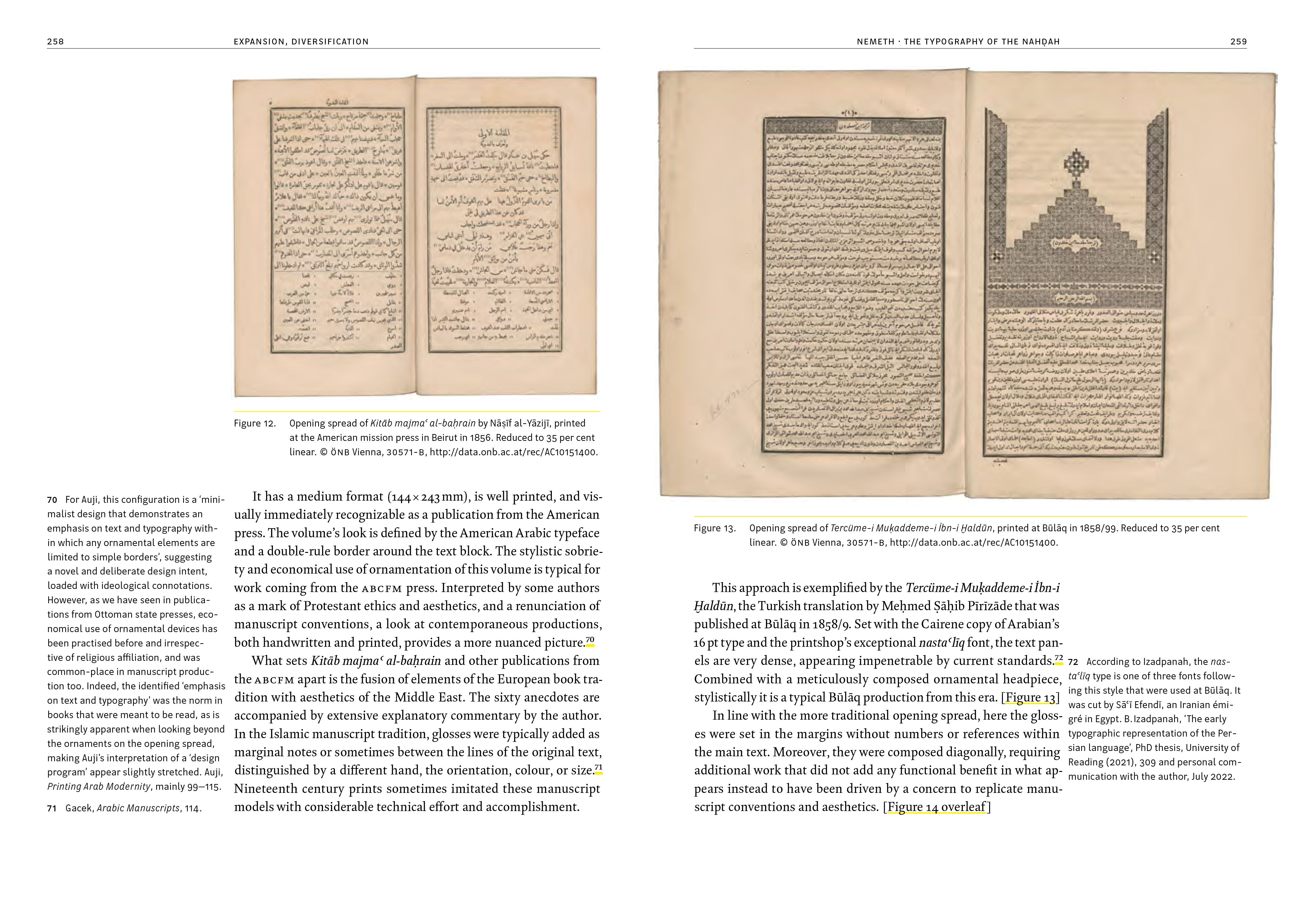

In my own historical essay, I investigate further the questions surrounding the contribution of typography to the emergence of the modern Middle East. Taking the Nahḍah — the movement of Arabic literary renewal — as its point of reference, the essay develops a typographic perspective of this central cultural phenomenon, investigating its material form. Thus it looks at the important and little explored role that the applied crafts of the printing trades played in the formation of the Nahḍah. Whilst focusing on the physical and visual characteristics of exemplary book productions of this era, the essay also considers the context in which they emerged. The essay touches on the technical, political, and economical influences that shaped the books of the Nahḍah, and explores the trade as an interregional network: tracing the fluid and often reciprocal influences of the publishing centres in Cairo, Beirut, and Istanbul. From the Mehāh-ı Miyāh (treatise of water), published in the 1790s, to a 1911 edition of Qāsim Amīn’s al-Marʾah al-Jadīdah, the essay charts the evolution of Arabic typography in the long nineteenth century. Through the examination of a dozen publications, the essay sheds light on various, instructive aspects of the history of Arabic typography during this important, foundational phase. Its central argument — that the typographic craft supplied the material fabric of the Nahḍah — is reiterated in the conclusion of the piece, arguing for a new appreciation of the role that the form of print played in the emergence of a modern Middle East.

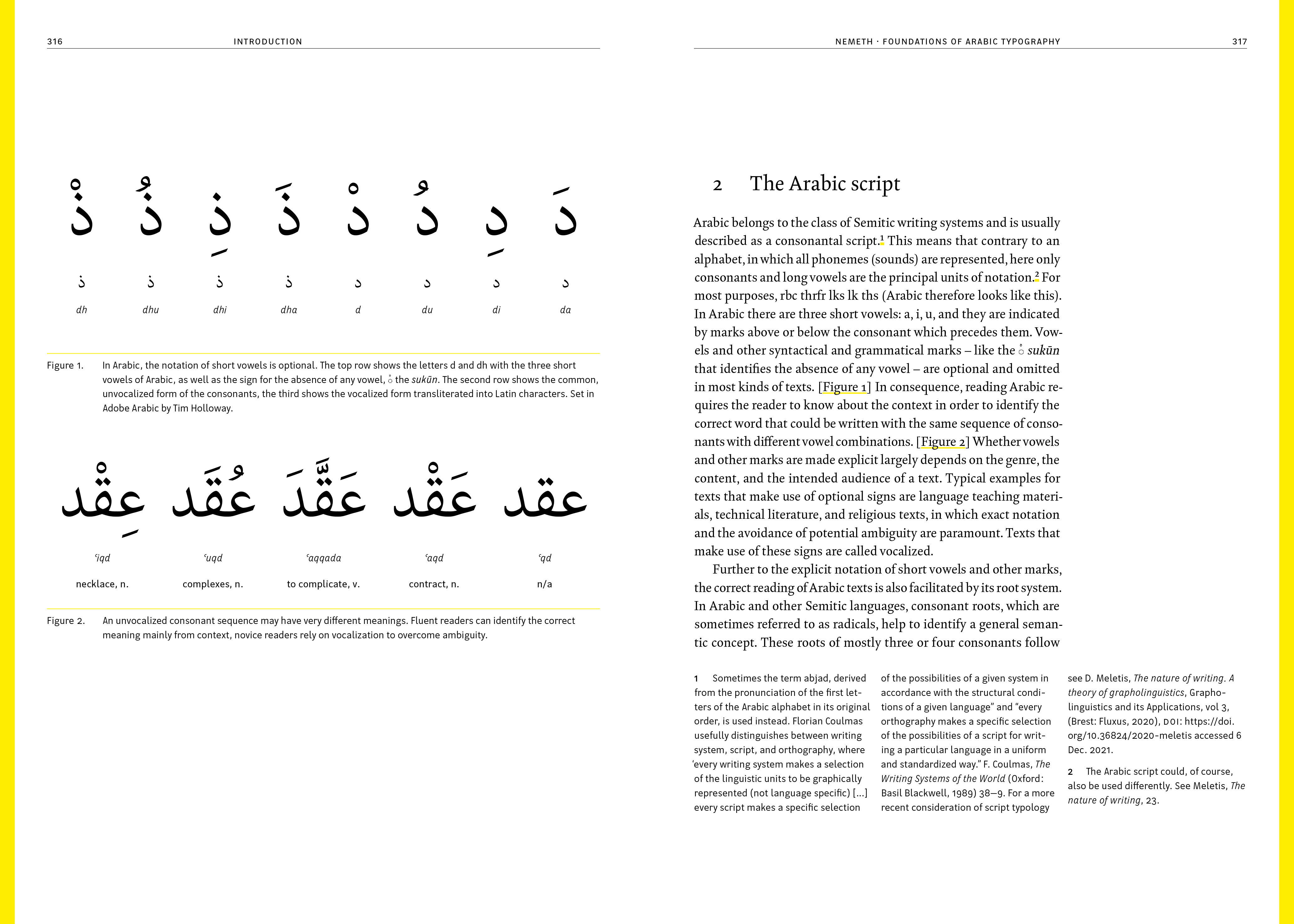

The second part of the book, ‘Foundations of Arabic typography’, focuses on the practice of Arabic typography. Inspired by Jost Hochuli’s concise classic (Detail in typography) it discusses central aspects of Arabic typographic design for practitioners. Principally conceived for students and designers who are not fully familiar with the Arabic script, it hopes to contribute to addressing a glaring gap in current literature. Whereas there are numerous, and often excellent guides and manuals on typography from a Western perspective, there are very few publications in English that are concerned with the use of type in other scripts. Yet, increasingly design practitioners are confronted with languages and scripts that they have not grown up with. Commonly, this encounter is biased towards a Western, Latin-centric design language. This is no fault of the protagonists, but the result of a lack of sound, comprehensive resources. ‘Foundations of Arabic typography’ therefore introduces the reader to central characteristics of the Arabic script, discusses some elements of its manuscript tradition, and considers key questions of micro-typography. It explores some of the nuts and bolts of text composition — measure, interlinear space, justification — and discusses the particularities of poetry and multilingual texts. It casts a critical view on some terminology and the suitability of design approaches, and offers some hands-on advice for a selection of use cases. Finally, with cross references from and to the historical studies in the first part of the book, ‘Foundations of Arabic typography’ exemplifies the concept of research-informed design.

Arabic Typography: History and Practice will be presented on 5 November 2022 in the context of a special issue of ISType in Istanbul. As first announced in September, the one-day conference will be hosted at the Sakıp Sabancı Museum and will interface leading authorities in Arabic typography and calligraphy with the book’s authors, weaving together perspectives from design, research, and interdisciplinary practices.

This post was first published on the TypoArabic blog.