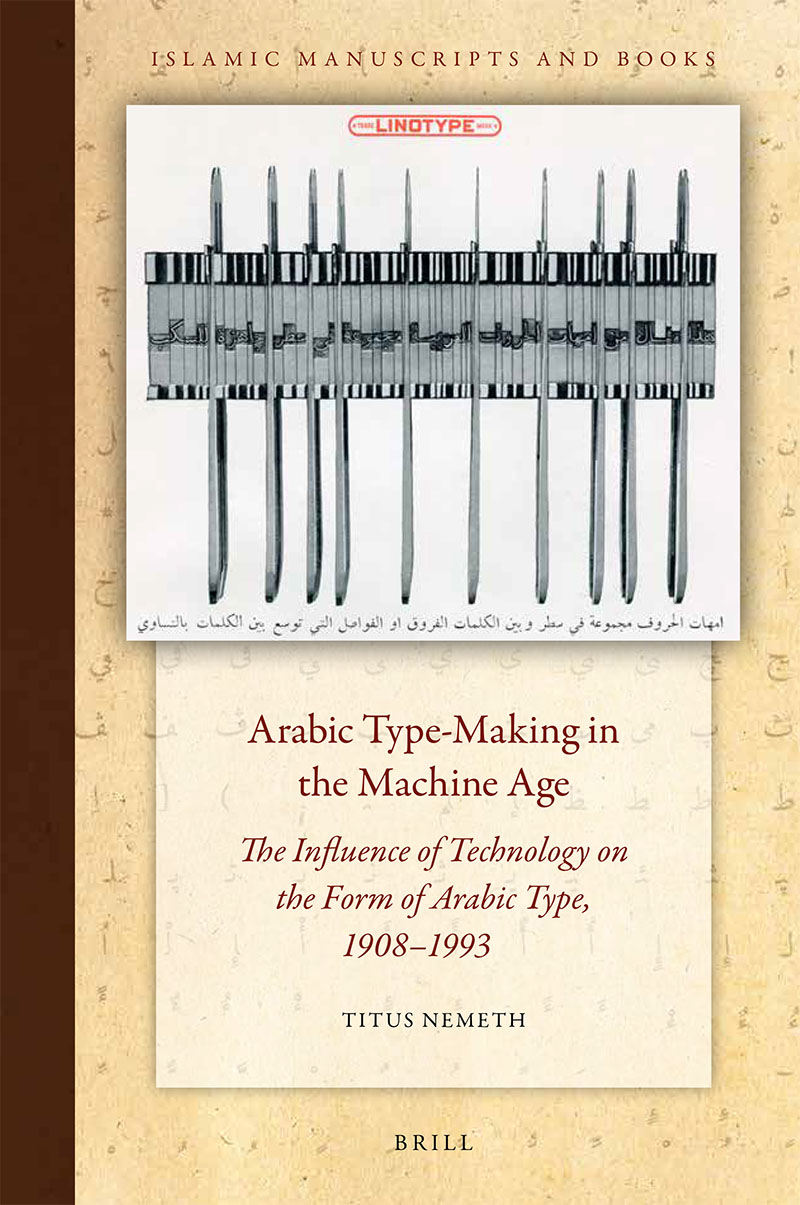

Last week I have submitted print-ready and ebook-ready files of my book Arabic Type-Making in the Machine Age: The influence of Technology on the Form of Arabic Type 1908–1993, which is going to be published by the Dutch publisher Brill next month. As the blurb says without any false modesty, this is the first in-depth account of the evolution of Arabic type in the twentieth century. Crucially, it is the first comprehensive study of the subject that is based on original archival research, documenting a wealth of previously unpublished and largely unknown evidence about the evolution of this field. Taking the characteristics of various type-making and typesetting technologies as its starting point, Arabic Type-Making in the Machine Age seeks to understand how typographic forms emerged under the impetus of limitations and constraints of machinery. It narrates how the predominantly Western manufacturers sought to provide typographic tools for the Arabic script, and investigates their various motivations, approaches, and solutions.

For the larger part of this history, Arabic type-making evolved against the backdrop of a dominant Western industry, with deeply entrenched ways of doing things, and technology that was never conceived to handle scripts with different characteristics than Latin. At the beginning of the twentieth century mechanisation meant progress – much like anything digital or ‘smart’ is considered an advancement of humanity today – and machines were seen as key for the path towards a better future. Beyond the immediately apparent advantages of speed and efficiency that mechanisation brought about, machinery indirectly promised to deliver achievements that are central for the formation of a public sphere: mass publication, general literacy, public debate, and consequently freedom of thought and speech. But whilst mechanisation was embraced for the progress that it embodied, it was not designed for Arabic, and imposed severe compromises. The Arabic script as it had evolved over hundreds of years thus had to be adapted, and was bent to the constraints of machines. In this process stylistic variety, principles of joining letters, methods of justification, rules of orthography, and concepts for the improvement of legibility were severely compromised, or entirely discarded, giving birth to a form of the script without antecedent in its written form.

Whilst in the 1910s the promise of inexpensive mass publication undoubtedly contributed to the acceptance of this previously unknown form of Arabic, it also marks the beginning of a problematic trajectory in the evolution of its typography. For if a form that was reduced to its bare, intelligible minimum could be used and sold as Arabic type, why would a profits-driven commercial enterprise go considerably further in its attempts to represent this script? Moreover, if the readers of a leading Arabic newspaper accepted it, couldn’t it be further simplified in order to increase composition speed, and thus reduce costs? For although common sense would suggest that advances in technology should bring improved products and results – ultimately achieving better typography for a better reading experience – the historical record does not validate this equation. As economic factors are central in all trades, also in the production of written communication it played and plays a decisive role, often stifling progress for Arabic typography. Here it is important to note that although the manufacturers of machinery and type were overwhelmingly from the West, it would be misleading to suggest that only their ignorance and thriftiness degraded Arabic type. Many initiatives for simplifications and the reduction of costs originated with the actual users of Arabic type, whether they were based in the US, the Lebanon or Iran. Moreover, once certain characteristics of Arabic type had become customary – primarily through use and lack of choice, rather than informed decisions – customer demand contributed to the spread and perpetuation of designs conceived for obsolete technologies.

In some cases, as for example with the introduction of photocomposition, new technologies barely achieved the typographical quality of its predecessors. As competition increased just after mid-century, the leading typesetting equipment manufacturers grappled with the increasing pace of technological developments, and some fared better than others. Whilst Linotype achieved a reasonably smooth transition towards photocomposition, and reviewed and updated its Arabic type library to take advantage of the possibilities new machinery offered, Monotype produced its finest Arabic type with hot-metal machines, and contributed little of quality thereafter.

Similar to technological advances, more competition and a diversification of the market are widely assumed to guarantee an improvement in the quality of products. Yet judging from the transition to digital type-making techniques, and the concurrent increase in the number of contributors and typefaces, this was not initially the case for Arabic typography. As the Desktop Publishing Revolution conclusively undermined the businesses of traditional type-making companies, the newly emerging digital world provided an empty playing field for new enterprises to fill – the alleged and hailed democratisation of the field. But as this competence-destroying technological upheaval unfolded, it also created a vacuum of expertise, which could not be replenished easily. Businesses and entrepreneurs of the digital world filled the space that was left by the retreating type-makers, with predictably poor results. In the 1980s companies emerged whose business model was to provide right-to-left composition on PCs, and mediocre means for vocalisation were celebrated as technological achievements. Thus, Arabic desktop publishing barely provided the functionality of Monotype hot-metal composition from the 1950s, and was far removed from the advanced capabilities of some dedicated digital typesetting systems, which were just rendered ‘obsolete’ by this latest revolution.

In parallel to these wider strands, the history of Arabic Type-Making in the Machine Age is dotted with exceptions, and projects by companies and individuals alike that defied the predominant logic of technological constraints and economic necessities. Whilst their success and influence on the field differed widely, some left lasting marks, and continue to do so. In this book some of them are given their place not only as a counterpoint to the mainstream, but are identified as the avant-garde, responsible for the most substantial progress of Arabic type-making and typography.

For me personally the publication of Arabic Type-Making in the Machine Age marks the closure of a process that started around mid-2009. Then I first contemplated pursuing PhD research into Arabic type history, and conversations with Fiona Ross and Jo De Baerdemaeker convinced me of the value and interest such an undertaking might have, and started my thinking about what and how I was going to investigate. Eight years later, I’ve come a long way – literally, and metaphorically. I’ve completed my PhD at Reading, moved around the world twice – from Paris to Reading, to Canberra, to Vienna – and still continued to pursue the research and work that led to this publication.

The present book is based on my PhD thesis, but was revised throughout. Not only did my proposal with Brill undergo the peer review process a scientific publisher provides – the reviewer’s remarks are acknowledged here – but I was fortunate that Christopher Burke kindly agreed to read drafts of the entire manuscript, helping me to refine arguments, coherence and language. Further to improvements in details, wider contextualisation and references to recent publications, two entirely new sections about Arabic desktop publishing tools, and the Dutch company DecoType fittingly rounded off the scope of the work.

Having my book published with Brill is an honour, and, may I say, an excellent fit. Over its 334 year history, no small part of its renown derived from its work in so-called Oriental languages and studies. Amongst its publications is for example the Encyclopaedia of Islam, the generally recognised standard work for Islamic studies. Arabic Type-Making in the Machine Age is published as volume 14 of the series Islamic Manuscripts and Books, finding itself in the company of some of the leading contemporary scholars of the arts of the book and the pen in the Islamic world. Besides its academic standing, Brill is more than conscious of the import of typography to convey content, as shown by its commissioning of the bespoke Brill typeface from John Hudson. As a fellow type designer, author, typesetter, and reader, I can only commend it for its ease of use and pleasure to read. Moreover, I am thrilled to say that my book will be printed in offset lithography, rather than in one of the increasingly prevalent print-on-demand techniques, and features numerous colour illustrations throughout its 550 pages. Moreover, for students and scholars whose institutions provide access to the ebook version, a print on demand copy for only 25€ can be ordered through Brill’s MyBook programme. Else, there is always Amazon.

My thanks are due to all those who have helped, in the most diverse ways, to make this publication happen. Whilst I have taken great care to purge all typos, errors, and omissions, no text is perfect, and I welcome criticism and corrections. Enjoy your read.